It’s been said that home is where the heart is. But what happens when the heart is broken, and an aggressor poses a foreseeable threat to other tenants, or the discord spills into other rental units and interferes with other tenants’ quiet enjoyment of the premises? Clearly, a rental property owner cannot be a social architect or mend broken relationships, but the owner does have certain duties and rights that may not be immediately clear when under the pressure of strife within their dwelling.

When a landlord encounters domestic violence in the property, the law prescribes what can and cannot be done to address this difficult topic and restore harmony to the dwelling. While it affords a great deal of tenant protections to domestic violence victims, the law also outlines tenant responsibilities to the landlord in a balancing act that recognizes the interests of both parties. First, some backdrop.

Long gone are the days of “don’t ask, don’t tell,” when domestic violence was a whispering subject of taboo. There’s been a seismic shift in public policy and the way law enforcement respond to domestic disturbances. Unlike the protocols of yesteryear when it was presumed that whoever raced to the phone first was the victim, determining who the aggressor is, is a factually complex and emotionally-charged decision that the police are tasked to make.

In tandem with the changing posture on domestic violence, more than ever, landlords must be aware of what is going on within their rental units and cannot turn a blind eye to infighting that can quickly reach a boiling point.

What is domestic violence, anyway?

California law seeks to prevent violence in familial or “intimate relationships,” a definition that has been expanded with shifting values and demographics. Domestic violence occurs when a spouse or former spouse, cohabitant or former cohabitant, an individual who is a parent of a child in common, or a dating partner, commits a criminal act of abuse. Aside from the “traditional” domestic charge against an intimate partner that is prohibited in California Penal Code Section 273.5, a host of other charges can arise, such as Simple Battery, Criminal Threats, Stalking, Sexual Battery, and more.

The legal definition of domestic violence can be found in a myriad of provisions within the Civil Code, Penal Code, or the Welfare and Institutions Code, and are broadly defined as “the act or acts of domestic violence, sexual assault, stalking, human trafficking, or abuse of an elder or a dependent adult.” For the purposes of this article, we’ll use the term domestic violence to encompass all forms of abuse.

Keep in mind, domestic violence can take many forms and it need not be the stereotypical slapping around — many times, an abuser uses more discreet methods of exerting control over the victim, through spoken, emotional or psychological means. For example, an utterance of, “I want to kill you” can potentially trigger domestic abuse, as well as stalking tactics after a relationship ends. While many acts of domestic abuse go unseen, let’s assume for the purposes of this discussion that the landlord knows there is something wrong.

However it rears its ugly head, domestic violence must be met with decisive action by owners. Failing to address these conflicts head-on can expose landlords to liability, due to the fundamental responsibility of rental housing providers to provide a safe and secure dwelling. When there is a foreseeable threat to tenants and the owner does not undertake proper measures to correct the abusive behavior of the aggressor or remove the person from the premises, and someone is later injured from the foreseeable threat, the landlord is partially culpable for turning the other cheek, in the eyes of the law.

Taking Proactive Measures

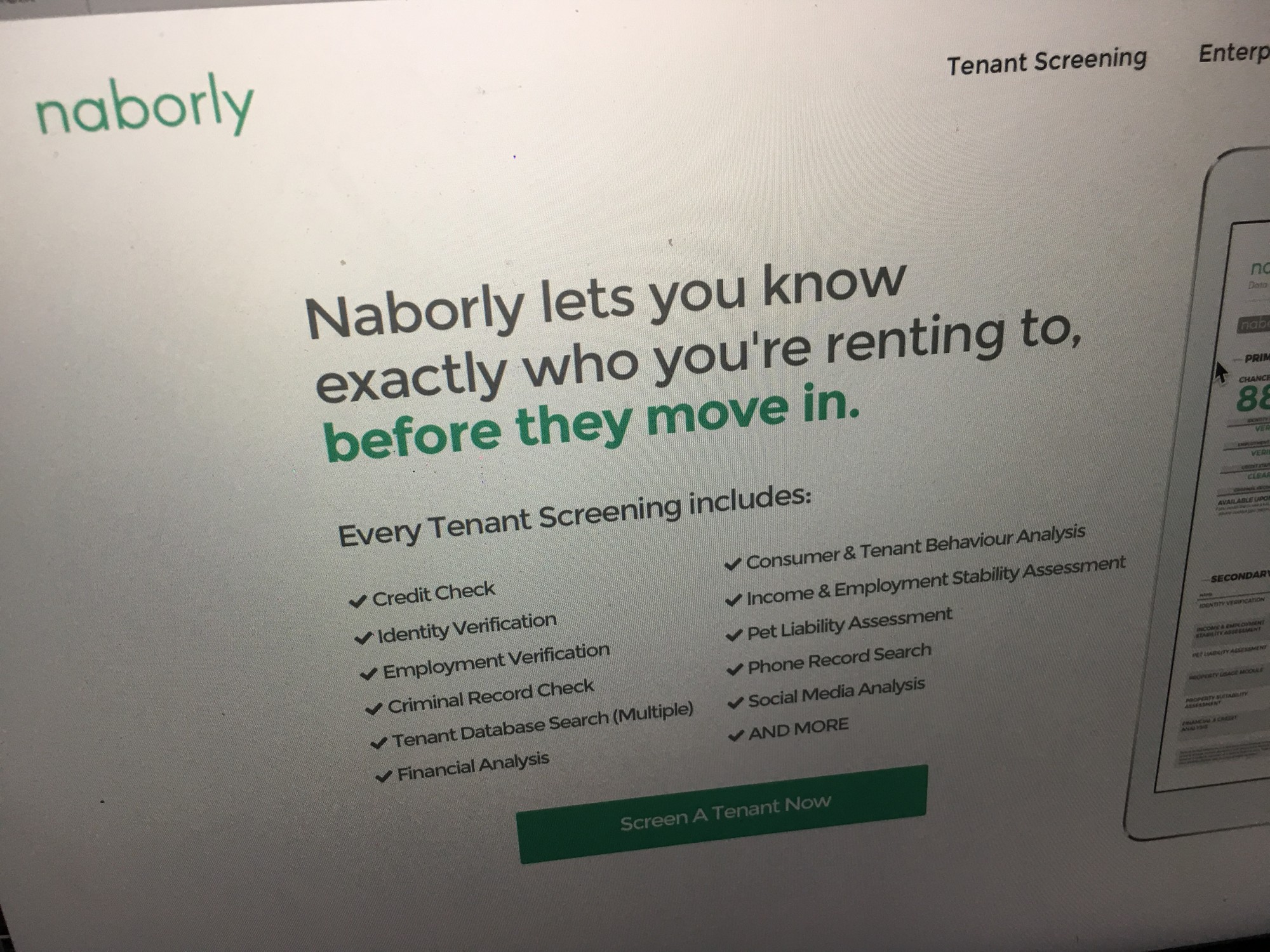

California Code of Civil Procedure §1161(3) allows the landlord to serve a 3-Day Notice to Quit when there are breaches to the rental agreement for something other than non-payment of rent, and this notice may be appropriate when a tenant commits domestic violence or sexual assault against another tenant or subtenant on the premises. Although perpetrating domestic violence is a permissible ground for serving the 3-Day notice, it must be properly served upon the tenant. A common theme we see at Bornstein Law is the improper service of notices that triggers a potential counterclaim of procedural missteps which could be avoided with the guidance of a real estate attorney.

Tenant Protections

A prevailing sentiment among lawmakers and regulators is that domestic violence victims should not lose their housing because of abuse or calling 911. This has been codified in California Code of Civil Procedure §§ 1161 & ,1161.3, which, with certain exceptions, prohibit a landlord from terminating a tenancy or refusing to renew the tenancy based solely upon acts of aggression that constitute domestic violence. This specific protection applies when the aggressor does not live in the same rental unit as the victim, perhaps an intimate partner who comes around but is not named in the lease.

A tenant’s mere assertion that he or she is a victim of domestic violence is not enough to invoke protections. The acts of domestic violence must be documented, as evidenced by one of the following ways.

- A temporary restraining order or emergency protective order lawfully issued within the last 180 days.

- A copy of a report, written within the last 180 days, by a peace officer employed by a state or local law enforcement agency acting in his or her official capacity, stating that the tenant or household member has filed a report alleging that he or she or the household member is a victim of domestic violence, sexual assault, or stalking.

Protection from Eviction & Exceptions

Although a landlord generally may not sever a tenancy or fail to renew the tenancy based only on acts of domestic violence perpetrated against the tenant, two notable exceptions apply. The law seems to recognize that protections should be given to genuine victims who need help, but not to those who have an “open door” policy of inviting the aggressor back into the rental unit. It also empowers the landlord to protect others within their rental unit. Thus, the delineated exceptions are:

- The tenant allows the person against whom the protective order has been issued or who was named in the police report as having committed the act or acts of domestic violence, sexual assault, stalking, human trafficking, or abuse of an elder or a dependent adult to visit the property.

- The landlord reasonably believes that the presence of the person against whom the protective order has been issued or who was named in the police report as having committed the act or acts of domestic violence, sexual assault, stalking, human trafficking, or abuse of an elder or dependent adult poses a physical threat to other tenants, guests, invitees, or licensees, or to a tenant’s right to quiet possession pursuant to Section 1927 of the Civil Code.

Still, the landlord must have previously given at least three days’ notice to the tenant to correct the violation.

Tenant’s Right To Terminate The Lease

Although in ordinary circumstances, the tenant may not prematurely end the tenancy, the law considers domestic violence an exigent circumstance. Civil Code Section 1946.7, then, allows the victim of domestic abuse to break the lease without penalty, though several caveats apply.

The survivor of domestic violence can provide the landlord a 14-day written notice of the intent to vacate, but must provide proper documentation that substantiates the incident. As indicated, it can be

“a copy of a lawfully issued temporary restraining order or emergency protective order that protects the tenant from further domestic violence, sexual assault, or stalking, or a copy of a written report by a peace officer employed by a state or local law enforcement agency acting in his or her official capacity, stating that the tenant or household member has filed a report alleging that he or she is a victim of domestic violence, sexual assault, or stalking.”

The underlying documents must have been generated within the past 180 days.

The Tenant’s obligation to pay rent

Provided that the proper and timely notice of the early lease termination is made with supporting documentation, the victim of domestic violence can move out without incurring the penalties incurred by other runaway tenants, but they are still obligated to pay the rent for no more than 14 days following the notice. If there are other tenants in the unit, their obligation to pay the rent continues unabated until the lease expires.

The laws surrounding domestic violence do not meddle with security deposit laws; the owner is not obligated to return any portion of the security deposit until the owner regains possession of the unit.

A few parting thoughts

We’ve only scratched the surface here, but we would be remiss not to remind landlords that given the sensitivity and volatile nature of domestic violence, they cannot disclose to a third party any information provided by the tenant unless the tenant consents in writing or is directed to do so by a court. The landlord may also have an obligation under the law to change the locks of the victims’ dwelling, a topic we will reserve for a future post. Although a landlord can evict the victim of domestic violence under only limited circumstances, these exceptions exist.

Finally, as if this area of law is not complicated enough, it can be muddled by issues that arise in terms of protective orders and court instructions, which may stipulate that the aggressor move out of the residence. Landlords are not expected to fully understand this morass in the normal scope of their rental business, making it imperative to consult with an attorney to navigate these perilous waters.

In over 23 years of managing landlord-tenant disputes, Bornstein Law been inserted into thousands of troublesome legal issues and domestic violence ranks amongst the most challenging. To equalize the situation and protect your rights as a property owner, contact our office today.