We were recently invited to give a speech about domestic violence in rental units in general, and specifically, HUD’s application of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), a federal law that has been instrumental in bringing the once taboo of subject of abusive relationships to light. Since it was signed into law by President Bill Clinton, VAWA has expanded in size and scope, as evolving social values have redefined domestic partnerships and recognized more subtle forms of abuse.

Aside from physical and sexual abuse, behaviors that arouse fear, prevent a partner from doing what they wish or force them to behave in ways against their will, acts of emotional abuse and economic deprivation, threats and intimidation, and stalking after the relationship has ended, can now be considered a serious situation requiring intervention, prosecution, or protections. The National Domestic Hotline has done an excellent job in depicting the ugly head of domestic violence and early warning signs here.

The goals of federal law and California law are in unison, though VAWA has the resources to bring courts, law enforcement, prosecutors, victim services and other advocacy groups, the private bar and other parties together to work alongside each other in a coordinated effort that typically cannot be achieved with the limited assets of state and local governments.

An added benefit of VAWA is that protection orders can be enforced across jurisdictional lines, under the legal term “full faith and credit,” meaning a court in any jurisdiction will honor and enforce orders issued by a court in other jurisdictions.

So, for example, a victim of domestic violence in Boise, Idaho has a protection order and flees to San Francisco to remove themselves from the abuser, but the offender relocates to San Francisco to catch up with the victim. With the added teeth of VAWA, Idaho’s order can be enforced in the newfound surroundings of San Francisco. Our friends at the Battered Women’s Justice Project expounds on the concept of full faith and credit in this PDF.

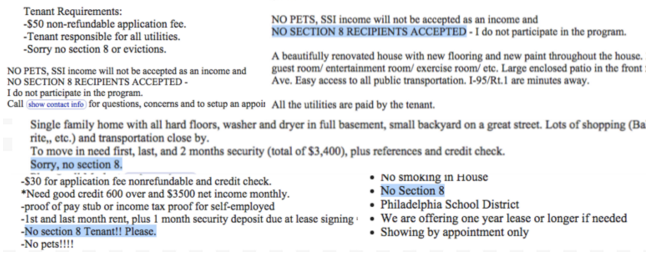

In an earlier article, we noted that Civil Procedure §§ 1161 & 1161.3 attempts to ensure tenants who are subjected to domestic violence are not victimized twice by prohibiting landlords from terminating a tenancy or refusing to renew the tenancy based purely on acts of aggression and seeking emergency assistance and this sentiment is shared by HUD – its stated position is that “nobody should have to choose between an unsafe home and no home at all.”

HUD has provided a framework to handle instances of domestic violence, and the first priority is to slay the beast. Once the perpetrator of domestic violence is removed from the rental unit, the question is whether the offender is the only resident who established eligibility for assistance.

Clearly, if the bad actor is the only tenant who qualifies for housing vouchers, they may leave close family members in the lurch. HUD takes a humanistic approach by giving other remaining tenants in the unit – husband, wife, sons, daughters, etc – the opportunity to qualify for housing voucher assistance, or give them enough time to find another place to live.

If someone asserts they are a victim of domestic violence or he or she is in imminent danger, they may seek to be transferred to another apartment if one is available.

To get the full scoop, get it straight from the source by downloading HUD-5380, the Notice of Occupancy Rights Under the Violence Against Women Act.

Parting thoughts

Under recent California law and also echoed in HUD guidelines, sufferers of domestic abuse do not have to jump through so many hoops as before to claim their status as a victim – the documentation requirements have been relaxed. In some cases, this means that tenants can bow out of the lease prematurely, without penalty. Add in the casualties of other occupants in the rental unit, this can become tricky.

Whenever domestic violence rears its ugly head, many issues arise, and rental property owners are not expected to fully understand the morass in the normal scope of operating their rental business. It’s been said that home is where the heart is, but when the heart is broken, what happen to the home? That’s a question best approached with Bornstein Law.